The chart that does not match you

You probably discovered the inaccurate medical records error because something routine went wrong: a prior authorization denied, a referral stalled, or an insurance letter citing a diagnosis you have never heard before. When you log into the portal, you find it there—on the problem list, in multiple notes—as if it has always been part of your story.

If you care for someone with chronic or complex illness, you quickly learn there are two versions of the past: the one you actually lived, and the one that exists inside the electronic health record. The chart is fast. It auto-fills, copies forward, and moves between systems. Your version requires explanation, repetition, and proof.

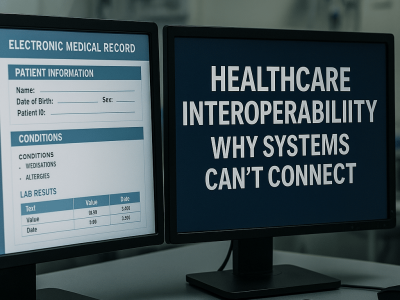

In a healthcare system built on electronic health records and data sharing, a single inaccurate diagnosis, allergy, or history entry can echo across clinics, hospitals, and insurers long before anyone notices—and long after it should have been fixed.

Key takeaways

- You have a legal right under HIPAA to request corrections (amendments) to inaccurate information in your medical record or electronic health record (EHR), but organizations can deny requests if they believe the entry is accurate and complete, did not create the record, or the item is outside the designated record set.

- Lawsuits usually do not arise from inaccurate documentation alone. Legal claims typically require that the error caused measurable harm—such as wrong treatment, delayed diagnosis, or financial loss—and that a provider did not act reasonably.

- Many EHR mistakes begin as second-hand information and then get copied forward across encounters. Widespread use of copy-and-paste and carry-forward features is a known driver of EHR errors and diagnostic mistakes.

- The most effective cleanup strategy is structured: obtain records from all major providers, document each error, use formal HIPAA amendment processes, and file a written statement of disagreement when corrections are refused.

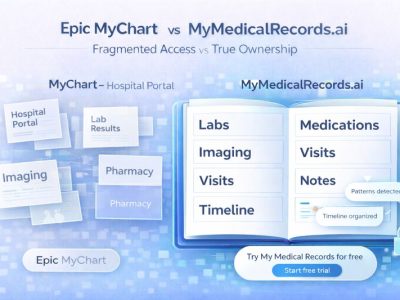

- AI tools and a patient-owned, longitudinal record can help you find contradictions quickly, prioritize high-risk issues, and maintain a single corrected source of truth you can share with new clinicians.

Can you sue for inaccurate medical records?

Most people’s first instinct is to ask whether they can sue over a false diagnosis or other chart error. The legal answer depends less on the existence of an error and more on what that error did to you.

The reality: errors alone are not enough

Courts and attorneys generally do not treat an inaccurate note or diagnosis code, by itself, as a standalone claim. Instead, the question is whether the inaccurate information contributed to malpractice or negligence. In practice, lawyers look for situations such as:

- A wrong or unnecessary treatment, procedure, or surgery that traces back to incorrect or outdated information in the chart

- An allergic reaction or serious side effect because the allergy list or medication list was wrong

- A misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis that allowed a condition to worsen

- Denied claims, large out-of-pocket costs, or lost employment opportunities linked to erroneous documentation

- Significant emotional distress and breakdown of trust when the error and its consequences are well-documented

The presence of an error matters, but so do two other elements: whether a clinician or organization acted unreasonably in creating or failing to correct it, and whether that failure clearly led to clinical or financial injury.

What attorneys actually look for

When evaluating a case based on inaccurate medical records, attorneys typically focus on three core elements:

- A clear, documented inaccuracy. There must be a specific entry or set of entries that are demonstrably wrong compared to the real history.

- Causation. There needs to be evidence that a clinician or organization did not act reasonably in documenting, verifying, or correcting the information.

- Demonstrable harm. The error must be tied to tangible injury—such as the wrong medication, a missed diagnosis, or serious financial harm.

If your immediate goal is to stay safe and receive appropriate care, it is usually more productive to ask: “How do I get this fixed and stop it from spreading?” The legal questions can be addressed in parallel if clear harm has already occurred.

Your HIPAA right to fix EHR errors

Under U.S. federal law, your main tool for correcting inaccurate medical records is the right to request an amendment to your protected health information in what HIPAA calls the “designated record set.” This is laid out in the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

What HIPAA actually guarantees

Under HIPAA, you have the right to:

- Request that a covered entity (such as a hospital, clinic, or health plan) amend information about you in its designated record set

- Expect the organization to have a written process for handling your amendment request

- Receive a written response that either accepts the amendment or explains a denial

Covered entities must act on your written amendment request within 60 days, with one possible 30-day extension if they provide a written explanation for the delay.

When organizations can deny your request for inaccurate medical records

A covered entity can legally deny your amendment request in several situations, including:

- The organization believes the information is already accurate and complete

- The organization did not create the record (and the original source is available to fix it)

- The item you want changed is not part of the designated record set, such as certain internal notes

- The information is not subject to access under HIPAA (for example, some categories of psychotherapy notes)

A denial can be frustrating, but it does not end your rights or options.

If your amendment is accepted

When the organization agrees to amend your record, it must:

- Add or electronically link your correction to the original entry so both are visible

- Ask you to identify any prior recipients of the erroneous information that you would like notified

- Make reasonable efforts to inform those recipients about the correction

This is important in a world of interconnected systems: if an error has already spread, the originating institution should help send the fix forward as well.

If your amendment is denied: the statement of disagreement

HIPAA gives you a way to formally push back even when a provider refuses to change the record. The basic sequence is:

- You receive a written denial that explains why the request was rejected and outlines your rights.

- You may submit a written “statement of disagreement” explaining why you believe the information is wrong or incomplete.

- The organization must add or link your statement to the disputed entry.

- Whenever the disputed information is disclosed in the future, your statement must travel with it, unless limited exceptions apply.

The organization can write a short rebuttal, but your statement remains attached to the record. In complex care and in litigation, that statement can function as a built-in second opinion from the patient or caregiver.

Why EHR errors are so persistent: second-hand data and copy-paste

Electronic health record errors are stubborn for two main reasons: clinicians often rely on prior documentation instead of re-verifying information, and EHR software makes it easy to copy forward large blocks of text and problem lists.

Second-hand sourcing: the echo chamber effect

In complex or chronic cases, clinicians routinely review outside records, summaries, and consultant notes. When they document a “history of” diagnosis, they may be repeating what another record says rather than independently confirming it with the patient.

If that original source was wrong, the error becomes amplified. Each new note points back to prior documentation as if it were a primary source. Over time, a single mislabeled diagnosis or misunderstanding can appear in multiple EHR systems, each one reinforcing the others.

Copy-paste and carry-forward: efficiency with a safety cost

Most major EHR platforms allow clinicians to:

- Copy forward prior notes

- Auto-populate problem lists and medication lists

- Reuse templated language for physical exams and histories

These tools speed up documentation but also move inaccurate data forward without re-verification. Errors get embedded into the structure of the chart and are carried along passively from encounter to encounter.

A structured cleanup strategy

If you have discovered significant inaccuracies and want to pursue corrections, here is a methodical approach that balances thoroughness with realistic time constraints.

Step 1: Gather records from all major providers

Request complete records—not just summaries or portal exports—from every hospital, specialist, and major clinic involved in the patient’s care. Look for:

- Full encounter notes and assessments

- Labs, imaging, and test results with dates

- Problem lists, medication lists, and allergy lists

- Discharge summaries and referral letters

Step 2: Build a timeline and error inventory

Create a chronological map of key events, diagnoses, and treatments. Then layer in the discrepancies:

- Which entries are wrong or unsupported?

- When did each error first appear?

- How far has each error spread?

Step 3: Prioritize by clinical and financial risk

Not every inaccuracy is equally urgent. Focus first on items that:

- Could affect treatment decisions or medication safety

- Appear on active problem lists shared across systems

- Have caused or could cause insurance denials or coverage issues

Step 4: Submit formal amendment requests

For each high-priority error, submit a written request to the appropriate organization using its official amendment process. Include:

- The specific entry or entries you want corrected

- Your explanation of why the information is inaccurate

- Supporting evidence (labs, imaging, second opinions)

Step 5: Follow up and file disagreement statements

Track responses. If an amendment is denied, consider filing a written statement of disagreement. Keep copies of all correspondence and decisions.

How AI tools can help you find and fix errors faster

AI models trained on medical language can assist with tasks that would otherwise require hours of manual review. They do not replace clinical judgment or legal advice, but they can accelerate your work significantly.

Use case 1: summarizing and comparing documents

AI can ingest dozens of records and produce structured summaries—organized by date, provider, or topic—faster than any human could. It can also flag obvious conflicts between different documents, such as:

- A diagnosis listed in one note that contradicts findings in another

- Medications listed as current in one system but discontinued in another

- Allergy entries that do not match across providers

Use case 2: identifying likely copy-paste propagation

AI can highlight text that appears nearly identical across multiple notes—suggesting it was copied without re-verification. It can also identify patterns such as:

- A diagnosis suddenly appearing in the chart without any corresponding workup

- Diagnoses that appear in one institution’s records but have no supporting notes, labs, or imaging

Items that appear repeatedly but are never discussed, updated, or reconciled are prime candidates for review and possible correction.

Use case 3: drafting amendment requests and summaries

Once you have annotated your own records, AI can help with the administrative writing:

- Turning your spreadsheet of errors into clear, respectful amendment letters tailored for each institution

- Building concise summaries of disputed histories that lay out your corrected timeline

- Creating side-by-side tables that show conflicting entries across different EHR systems

AI should remain your assistant, not an autonomous agent. You stay in charge of what is sent, to whom, and with what supporting evidence.

How a patient-owned record changes the power dynamic

Even if every organization perfectly followed HIPAA, your records would still be fragmented. A patient-owned record acts as a hub: a single, longitudinal version of your health story that you curate and control.

1. You maintain the master version

Instead of trusting each EHR to be accurate, you maintain your own master record that:

- Pulls in information from hospitals, clinics, labs, and insurers

- Lets you annotate or override entries you know are wrong or outdated

- Allows you to highlight what truly matters—current diagnoses, medications, allergies, key test results, and major events

When a new clinician asks for your records, you can send a curated snapshot instead of hundreds of pages of conflicting PDFs. This instantly signals that you have done the work to verify your history.

2. You can track and manage disputes

For every disputed entry, your patient-owned record can store:

- The original erroneous text and its source (organization, date, document type)

- The evidence that supports your corrected version

- Copies of the amendment requests you sent

- Responses from each organization

- Any statements of disagreement you filed

Over time, this becomes a structured case file that is far easier for new clinicians—or attorneys—to understand than scattered emails, phone notes, and portal messages.

3. You reduce future propagation of errors

When you see a new specialist, you do not have to let their system blindly import the same flawed problem list or medication list. Instead, you can:

- Share your reconciled snapshot as a starting point

- Explain which items have been disputed or corrected elsewhere

- Provide documentation that supports your curated version

When one organization finally fixes an error, you update your hub once. From there, you can see which other systems are still out of sync and decide where to focus next. HIPAA gives you the right to request corrections one organization at a time; a patient-owned record gives you power to operationalize truth across all of them.

Three concrete actions this month

If the whole process feels overwhelming, focus on a short, time-boxed plan.

1. Run a “record truth audit”

Pull these lists from every major portal:

- Active problem list

- Medication list

- Allergies and adverse reactions

Put them side by side in a simple table and highlight contradictions, obvious errors, and outdated information. Many people discover at least five to fifteen issues worth investigating in a single hour.

2. File formal amendments for your top three high-risk errors

Start with anything that could immediately affect your safety or care:

- Wrong diagnosis that drives current treatment decisions

- Wrong allergy or serious drug reaction

- Wrong medication or dose

- A major past event (for example, stroke, seizure, or heart attack) documented incorrectly

Use each institution’s amendment form, attach supporting documentation, and keep copies. Set a reminder for about 65 days from submission to check whether you have received a response.

3. Begin building your own longitudinal record

You do not need a perfect system to start. Options include:

- A secure, shared document or spreadsheet you control

- Exports from your portals that you organize by time and topic

- A dedicated patient-owned record platform, such as MyMedicalRecords or similar tools designed for longitudinal tracking

As you layer AI-assisted checks on top of this organized record, you will notice discrepancies faster and prevent outdated information from quietly turning into “facts” about you.

FAQ: common questions about medical records errors

How long does it take to correct the inaccurate medical records?

Under HIPAA, organizations generally have 60 days to act on a written amendment request, with one possible 30-day extension if they explain the delay in writing. Actual timelines vary by institution, but if you have not heard back within that window, it is appropriate to follow up with the medical records department or privacy office.

What happens if a medical record error caused wrong treatment?

If an inaccurate entry contributed to a wrong or delayed diagnosis, incorrect treatment, or serious financial harm, you may have both safety and legal issues to address. In addition to using amendment and disagreement processes to correct the record, consider:

- Asking your current clinicians to document the corrected understanding of your condition

- Requesting copies of all relevant records and keeping your own timeline of what happened

- Consulting an attorney experienced in medical malpractice or patient-rights law in your state to understand your options

Correcting the chart is important both for future care and for any formal complaint or claim you may pursue.

What if the medical record error is in a document I did not create (like a specialist’s note or hospital discharge summary)?

This is one of the most common roadblocks patients encounter. Under HIPAA, a covered entity can deny your amendment request if it did not create the record and the original source is available to amend it. For example:

A hospital’s amendment office may say: “That specialist’s note was created by Dr. Smith at Specialty Clinic, not by us. You need to contact them directly.”

A primary care practice may say: “That discharge summary came from the hospital. We cannot amend records we did not write.”

What this means in practice:

You may need to file separate amendment requests with each organization that contributed to your records. If a diagnostic error appears in a consultant’s note that was then copied into your primary care record, both the original creator and the organizations that imported it should be asked to correct it.

Your options:

- Contact the originating organization first. If the error is in a specialist’s report or hospital note, request amendments directly from that source.

- Ask each organization to notify recipients. If one organization corrects an error, HIPAA requires them to make “reasonable efforts” to notify other recipients of the original erroneous information.

- File a statement of disagreement with each institution. If the originating provider refuses to amend but acknowledges receiving your request, you can file a disagreement with them. Then, ask secondary institutions (such as your primary care provider who received a copy) to attach your disagreement to their copy as well.

- Document the chain in your patient-owned record. Keep a master list showing which organization created each entry, when you requested corrections, and their responses. This makes it clear to new clinicians that errors have been disputed even if not corrected everywhere.

The fragmented system means patience and follow-up are essential, but you have the right to pursue corrections at the source.

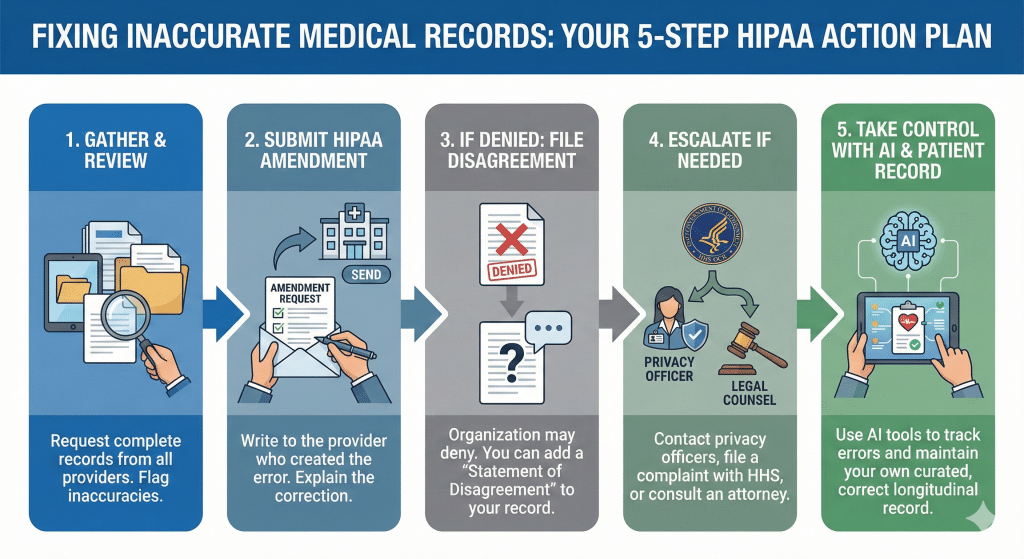

Infographic description: A horizontal flowchart showing five steps to fix inaccurate medical records and EHR errors: (1) gather records from all providers, (2) review and flag suspected errors, (3) submit formal HIPAA amendment requests, (4) file a written statement of disagreement if requests are denied, and (5) escalate to privacy officers, HHS OCR, and legal counsel when needed. The final panel shows AI tools and a patient-owned record helping to monitor and reconcile information over time.

The bottom line

Inaccurate medical records and EHR mistakes are not just annoying; they can change how clinicians see you, which treatments you receive, and how insurers judge your claims. The same features that make electronic records efficient—data sharing, templates, and copy-paste—also let errors spread quickly, while the correction process remains slow and manual.

You do have rights: HIPAA gives you a structured way to request amendments, attach your own statement of disagreement, and escalate if those rights are ignored. AI tools and a patient-owned record give you additional leverage, helping you maintain a single, curated source of truth about your health and prevent someone else’s mistake from becoming your permanent diagnosis.

[1] 45 CFR Section 164.526. Amendment of Protected Health Information. U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-C/part-164/subpart-E/section-164.526 VERIFIED ✓

[2] Cornell Law School. 45 CFR Section 164.526 – Amendment of protected health information. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/45/164.526 VERIFIED ✓

[3] American Retrieval. Can You Sue for Inaccurate Medical Records? https://americanretrieval.com/blog/can-you-sue-for-inaccurate-medical-records/ VERIFIED ✓

[4] Verywell Health. How to Correct Errors in Your Medical Records https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-correct-medical-record-errors-2615506 VERIFIED ✓ (accessed via search)

[5] Khela, H., Khalil, J., Daxon, N., et al.. Real world challenges in maintaining data integrity in electronic health records. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2024;29:100233. PMCID: PMC10824972 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10824972/ VERIFIED ✓ – Finding: 15% of charts contained errors; 2.6% of EHR errors lead to unplanned care

[6] Tsou, A.Y., Lehmann, C.U., Michel, J., et al.. Safe Practices for Copy and Paste in the EHR: Systematic Review, Recommendations, and Novel Model. Appl Clin Inform. 2017 Jan 11;8(1):12-34. PMCID: PMC5373750 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5373750/ VERIFIED ✓ – Finding: 66-90% of clinicians use copy and paste; 2.6% of diagnostic errors

[7] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Individuals’ Right under HIPAA to Access their Health Information. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/access/index.html VERIFIED ✓

[8] Verywell Health. How to Correct Errors in Your Medical Records https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-correct-medical-record-errors-2615506 VERIFIED ✓

[9] NC Medical Board. Amending Your Medical Records https://www.ncmedboard.org/resources-information/consumer-resources/smart-patient-toolkit/amending-your-medical-records VERIFIED ✓ (verified via search)

[10] Clinion. Clinical Data Validation with AI: Enhance Accuracy & Compliance. https://www.clinion.com/insight/clinical-trial-data-validation-with-ai/ VERIFIED ✓

[11] EvolutionIQ. How Conflicts and Discrepancies in Medical Records Add to Case Complexity. https://www.evolutioniq.com/resources/how-conflicts-discrepancies-in-medical-records-add-to-case-complexity VERIFIED ✓

[12] Bricker & Gray Don, PLLC. When Can a Covered Entity Deny a Request to Amend PHI? https://www.brickergraydon.com/insights/resources/key/HIPAA-Privacy-Regulations-Amendment-of-Protected-Health-Information-Denying VERIFIED ✓

[13] Sturgill Turner. Balancing Confidentiality and Compliance: HIPAA and PHI Amendment. https://www.sturgillturner.com/our-insights/phi-amendment-hipaa-rules VERIFIED ✓

[14] U.S. HHS OCR. Individuals’ Right under HIPAA to Access Their Health Information. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/access/index.html VERIFIED ✓

[15] NewYork-Presbyterian. Accessing Medical Records – Amendments. https://www.nyp.org/patients-visitors/medical-records/amendments VERIFIED ✓ (accessible via search)

[16] NYU Langone Health. Request to Amend Protected Health Information (PHI). https://nyulangone.org/files/request-to-amend-phi.pdf VERIFIED ✓ (accessible via search)